A college professor responds: This American Life #562, #563

/The recent two-part This American Life program "The Problem We All Live With" generated a lot of buzz. More than being buzzworthy, though, the investigation offered a real solution to education in America, however difficult it has been and may be to employ. It's so hard for journalism to not offer a thesis statement in order to appear balanced. But this program did more than peel back a few rotting floorboards on schools, which is oftentimes what education reports tend to do. It offered listeners a well-tested theory, a theory that seems so basic that it's laughable: Integration is the most powerful way to bridge the achievement gap between underresourced and well-resourced schools. Period.

It's much easier, one reporter noted, to dream up fixes for failing schools than it is to try to dismantle the systemic racism and classicism that rendered certain schools a failure.

I can get behind this. Even though I've spent less than 10% of my entire student life in public school. I believe in integration not just as an ideal but as a cornerstone of effective education.

I teach at a private university with roughly 40% students of color. It's a pleasure and a privilege to teach this mix of students. We build circles of trust in classes, in residence halls, in intramural sports, in clubs and the hope is that those circles enlarge to spheres much greater than our little campus. Prior to this gig, I taught at a diverse, urban community college. Most--not some--of my students spoke English as a second language. I taught English composition which was a delight since so many students could empathize with one another in the struggle to master another language. My classes came ready-made integrated. College is obviously elective, unlike public schools grades K-12 in which teachers must educate every child. Still, I agree with the findings of TAL: integration is the clutch in the manual car driving us toward educational reform.

But as TAL's reporting demonstrated, integration is the hard-fought battle, often trying to sell school integration without attaching it to the stigma of busing and without tokenizing students. Ayeeee. Hand me that magic wand....

The reason I believe so much in the power of integration goes well beyond my time in the classroom, however. I identified especially with TAL's coverage of parents expecting so much of schools that they "hand-picked" them. Parenting in America has swung so far to extreme protectiveness that schools seem to get stuck in a holding pattern of incubation rather than true education. Are parents in 2015 truly excited about the heightened challenges of their kids' classes or about the independence their children are gaining through projects and extra-curriculars? It does not appear that way, from the little I've gauged. Parents do their kids' entire projects for them. They "coach" by teaching their kids the position for which they want their kid to specialize. Rather than have their child experience the chagrin of sloppy penmanship or the pride of a job completed by hand--the pervasive attitude for parents seems to be akin to the LA Police Department: serve and protect.

Schools have become like restaurants rated on Yelp.com. Friendly service and immaculate facilities will earn high marks. High expectations of students and varied social dynamics are not always comfortable for patrons. Maybe the place down the road will be better--I hear they have even have a Groupon.

Universities are regarded as country clubs that exist to furnish four-star accommodations and luxury amenities. My students will rate me on the ease with which I grade assignments, the accessibility of my lectures, the availability of me in my free time. It is not enough to teach; teachers must aim to please.

Which is why I think TAL's program sounds the battle hymn for every teacher. We are helping to prepare a generation of students who will need to be problem solvers--solutionaries, if you will. These students will need to experience integration, which may (gasp) entail discomfort. These students will need to learn how to resolve conflicts and stand up for their beliefs. They may even need to learn to innovate using a limited budget, versus waiting for their parents to find something suitable on Pinterest to copy.

It's never our goal to fail: our kids, our schools, our communities. But there's an awful lot to learn through failure, largely so that we don't make the same mistakes--systemic and microscopic alike--again.

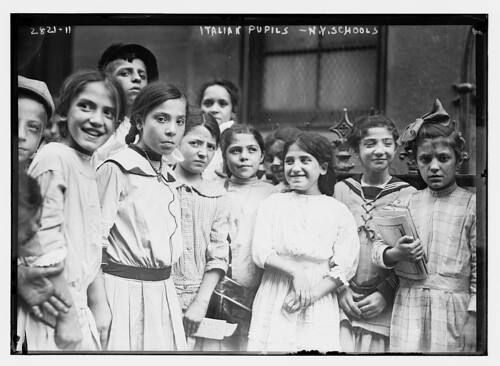

![[African American school children entering the Mary E. Branch School at S. Main Street and Griffin Boulevard, Farmville, Prince Edward County, Virginia] (LOC)](https://farm3.staticflickr.com/2948/15356487161_c85e8a2eff.jpg)