Six Years a Southerner

/"Looks like Michelangelo is getting a bath," said the dad, bending over the grate where his offspring had wedged an action figure into a ground sewage stream. "Do y'all understand how this happened?" One of the funniest scenes during our time in the South played out within the first month of our arrival, some six years ago. Loverpants and I still laugh when we walk by this spot in front of the Tennessee Aquarium, a destination that is the heart of Chattanooga's renaissance as a Southern city. We think how the aquarium houses pods and plants and all manner of sea and river creatures. It also the little-known bathhouse of ninja turtles.

My own immersion into the South was almost as abrupt as Michelangelo's. We arrived to our rented ranch house on three acres and felt the distinct awe of our new rural-burbia life, waking up to the sounds of cows mooing when only days prior, we had known only tinkering shopping carts rattling down city blocks, the siren cry of ambulances so familiar we barely noticed. We were soon introduced as newcomers to my workplace. We were awkward and unwieldy. Baby Girl couldn't find her sleep groove for weeks. I couldn't find time to lesson plan. Loverpants couldn't find an office space to lease. Little Man couldn't find his walking feet.

But then we did. We found ourselves doing life in the South as people who worked and churched and bought Aretha Frankenstein pancake mix to make at home on Sunday mornings. The difference, I think, is that finding a rhythm is not the same as finding a fit, which is how I would classify my time in the South. Just because Michelangelo is placed in the gutter and he stays there doesn't mean he belongs there.

I have not found belonging in the South. This is not a criticism of the South, just a witness to my experience. Mercifully, though, I have found pockets of being known and that has been the great treasure of my life here.

Belonging in the South, specifically in a more junior city, specifically in a conservative religious community, requires a certain extroversion that eludes me. Small talk is currency in this environment where one mills in small concentric circles of interconnected folks. I am allergic to small talk so I am most likely to enter into conversation with, "I cannot freaking believe I am buying sex ed talk books for my kid already," rather than preferred pleasantries about the weather. There is also a pervasive lack of directness that is borne of the aforementioned interconnected network. If good fences make good neighbors, then a lack of fencing can lead to a superficial neighborliness. Being authentic, after all, is a liability. And being authentic in one social circle where any misdeeds in one patch might bleed into another can leave us defenseless. The need to "play nice" at the expense of addressing conflict or wrong behavior is something I've observed too often. My natural bent is to be as direct as possible, even if it is hard. So whenever I have found others willing to join me to climb the chutes and slide down the ladders of directness, I have desired to call those people my kin.

There are a whole host of other aspects that I have found so foreign about the South (The expression "might could." The frequent use of styrofoam in restaurants. The lack of sprinkler parks in spite of the heat much of the year). But if I dwell on these things then I fail to see the good and to celebrate the great things about the American Southeast (Publix Grocery Stores, hallelujah! The lushness of spring. Savannah/Tybee Island. Charleston. Birmingham. Nashville. Memphis. Crepe Myrtles. Sitting in the bleachers for Used Car Night at a minor league baseball game in the fall). There is so much to adore about this region that has been our home for six years, this city that has, at turns confused and enchanted us.

We will return to the Northeast from whence we came, with children six years older, with wisdom poured like a fine wine aged six years. And we will be glad for the friends we have made, the places we have served, the houses where we have worshiped. We will count it all a blessing to not only have gotten wet but to have been fully immersed like Michelangelo in the sewer, with passersby asking if y'all knew how it happened.

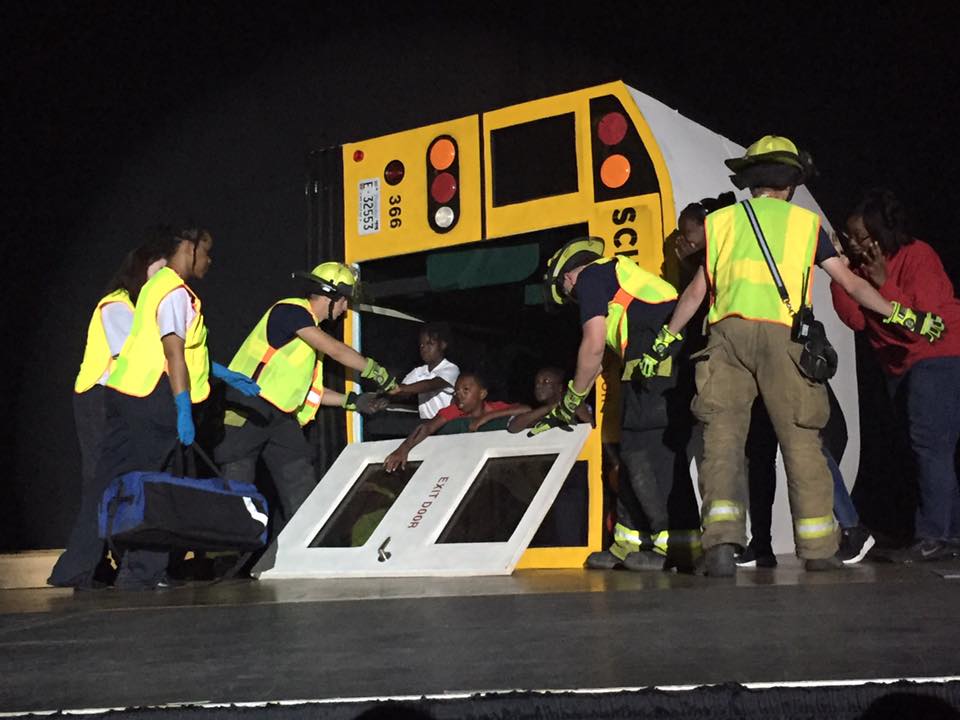

Christ came to save us all: the tattooed and the trucker hatted; the schoolbus driver and the new teen driver; the gun-toting soldier and the refugee. He would not let one fall to the ground without regarding it as precious. Not a sparrow falls without his notice. In the same vein, this flag that we revere, the one we cannot let fall to the ground, is one for which blood was shed so that all could enjoy freedom. What could be freer than love? Freedom and love are regularly compromised and trampled on the battlefield for our hearts, but the war has already been won by the One.

Christ came to save us all: the tattooed and the trucker hatted; the schoolbus driver and the new teen driver; the gun-toting soldier and the refugee. He would not let one fall to the ground without regarding it as precious. Not a sparrow falls without his notice. In the same vein, this flag that we revere, the one we cannot let fall to the ground, is one for which blood was shed so that all could enjoy freedom. What could be freer than love? Freedom and love are regularly compromised and trampled on the battlefield for our hearts, but the war has already been won by the One.