On my experience as an LGBTQ ally at SAU

/“Love keeps no record of wrong.” Since my departure from Southern Adventist University in 2016, I have pondered the words of Paul to the Corinthians as I worked through my feelings of sadness, hurt, and confusion, knowing that the kind of love Jesus offers us is liberating, and that liberation comes through reconciliation.

However, I have also pondered the Golden Rule. To treat others as I would want to be treated. I have resolved to tell my story, even though it records wrongs, as I would not wish for others to have had the same experiences I had as an employee of SAU.

I should first establish that I voluntarily left Southern after five years of full-time employment as a professor. I was not “invited to resign” nor did I depart on the grounds explained by other euphemisms. I left to take a job at another school because I was tired of fighting the same battles at Southern, tired of constantly feeling frustrated and that my job would be placed in jeopardy because of the marginalized students for whom I cared and advocated.

I would also like to establish that I did not grow up in the Adventist church. I was raised Catholic, attended primarily Catholic Schools and converted to Seventh-day Adventism when I was 23 years-old after attending an Adventist Church and feeling convicted at GYC in 2003 that a biblical faith was what I wanted to pursue for the rest of my life. I received my master’s degree from Harvard University and taught at a community college prior to joining the faculty of Southern in 2011.

For five years, I worked hard and taught students who were bright and generally hardworking and mission-minded. I adored so many of my colleagues and was inspired by their interesting research and their total dedication to student success. I was promoted to associate professor after submitting my portfolio for review. However, because I did not have a terminal degree, I would need to pursue one in order to be able to be eligible for promotion or apply for sabbatical. As fewer and fewer of my colleagues were being released of coursework to pursue terminal degrees, I began to consider different prospects for myself and my family.

More importantly, though, I was finding the culture at SAU toward LGBTQ students deeply troubling on campus. I would estimate having at least one student per semester in one of my classes who self-identified as LGBTQ. These students were active in Campus Ministries and community service, were excellent students earning high marks.

And they often sat in my office weeping.

They were consistently harassed in the dorms, they said. They were maligned on social media. They did not feel safe engaging in campus-wide or in class dialogues or even in seeking counseling on campus for fear of being reported to their deans or their parents (were their concerns unfounded? I would like to believe so).

I could list a great many upsetting incidents to which I was privy as a faculty member on Southern’s campus, but these would not be productive and may only make me seem embittered. I did find the leadership of Former President of SAU Gordon Bietz to have a loving posture toward LGBTQ students. He welcomed them into his office and did not discourage them from meeting as group as he understood the need to be in solidarity with one another, although he made it clear to the LGBTQ group SHIELD that they would not be eligible for funding through the Student Association budget. (My time with current president David Smith did not overlap more than a couple of months.) I did not, however, find the leadership of some others on SAU’s Administration to be as loving toward LGBTQ students. I and another of my colleagues were warned not to invite the SHIELD students to gather for worship in our homes because of the message that might signal to the community.

Wrap your mind around that message for a moment. Replace LGBTQ with "struggling with disordered eating" or "homesick" or “sexually promiscuous” or “substance abusing” students and you will see the hypocrisy of the messaging around those to whom Southern’s faculty were encouraged to minister. It’s inconvenient when the tendencies, behaviors, or even the sexuality of people in a community do not align with one’s branding. I’m sure Jesus felt this profoundly true to his leading of the Twelve Apostles. But he loved and led and invested in and died for them anyway.

One incident that highlights this hypocrisy most prominently was when I was departing Southern. As I was preparing to depart from my position (I had already cleaned out my office), a current student reached out to me and told me a story of an LGBTQ student who had just arrived on campus as a new student during the Smart Start summer session. This student had been so harassed by students he’d never met in the dining hall, blocked from moving through the cafeteria line and called “fag” tauntingly to his face, he was in a state of shock. He did not know a soul on campus and was already being harassed. I decided to make the faculty body aware of the terms of this incident, because, from my view, there didn’t seem to be any reason to hold it under my hat. If it was true, the community had a responsibility to respond. It if were falsely reported, the community needed to take stock of what the response should be if it ever did occur.

In sharing the alleged incident with the faculty via an online listserv, the response was overwhelmingly kind. Prayers and offers of support swelled via e-mail for the student and the faculty body was unilaterally sad to learn that a student had been mistreated. Then an elder male colleague (whom, I should disclose, I had never had a poor interaction with and who appeared to never know my name when I introduced myself to him, even after giving his daughter rides and working in the same building for five years) shot back. He said that reporting an allegation of this nature was patently wrong and that I was, “Unfit for higher education.” This was not the parting gift I had hoped for in leaving Southern. Nor was his complete lack of apology for excoriating me among my colleagues as “unfit.” Yet, I am grateful for the experience as it allowed me to experience what our LGBTQ students experience on Adventist campuses every day: being made to feel “unfit” by some administrators, faculty members, and peers who lack the compassion and wherewithal to love them well. In five years, I never heard a single LGBTQ student ask for any sexual promiscuity to be condoned. I never heard them asking for a change of biblical language or policy. I only ever heard them want to be loved: by their teachers, peers, and even by their parents. Sometimes they just wanted to meet as a body of students to discuss their lives on campus. Sometimes they were only asking for a forum.

There is signage in the Hulsey Wellness Center on Southern’s campus that greets all who enter. It says, “Fit for Eternity.” It has often struck me as clever, though egregiously inaccurate. We are all -- regardless of sexual orientation, diet, language or creed -- abysmally unfit for Eternity. It is only through the matchless love of Christ that we can be made whole, that we can be made well, that we can be deemed fit to share in the bounty of his riches. I cannot wait for the day when he would only speak the word to make us - you, me, and all my former students - fit to share in his glory.

I am wishing the current graduating class a happy graduation weekend and want to encourage them to continue to go forth as lightbearers, and to never be afraid to love others well.

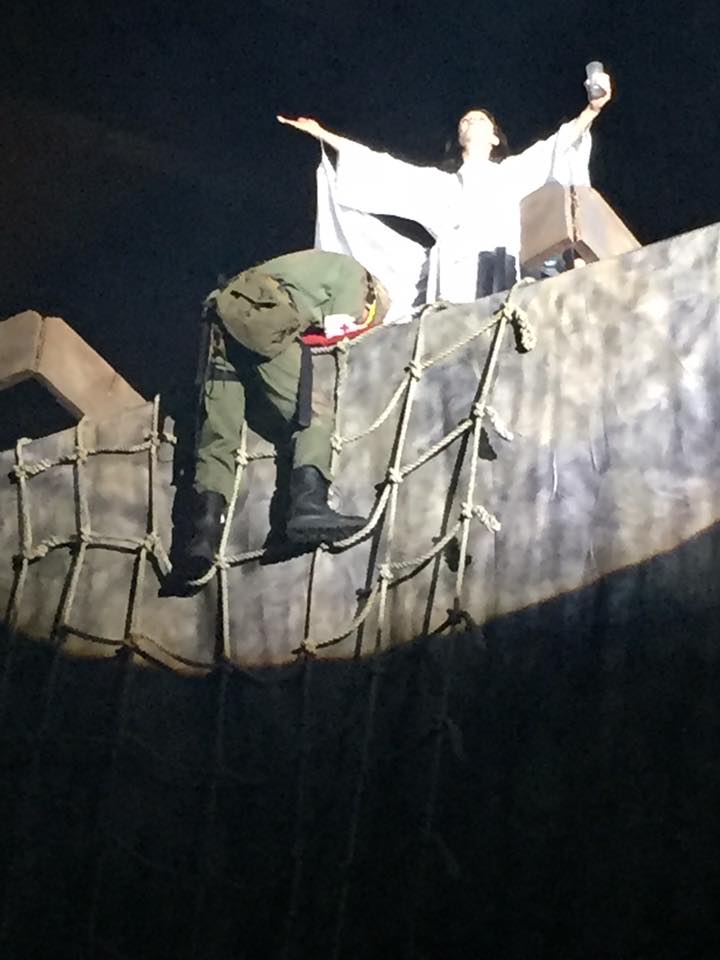

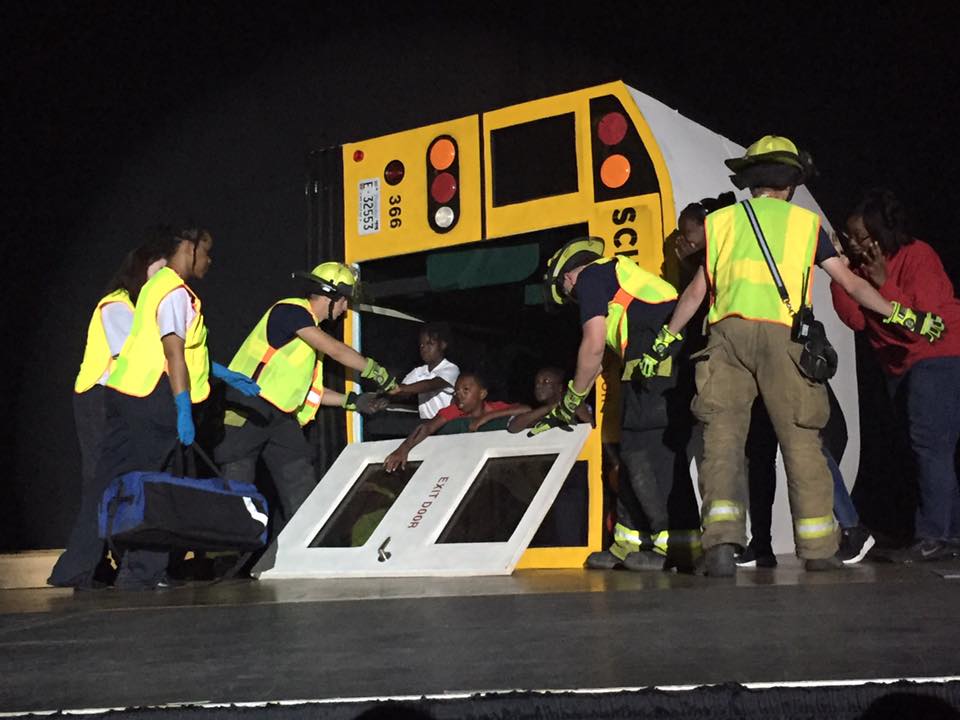

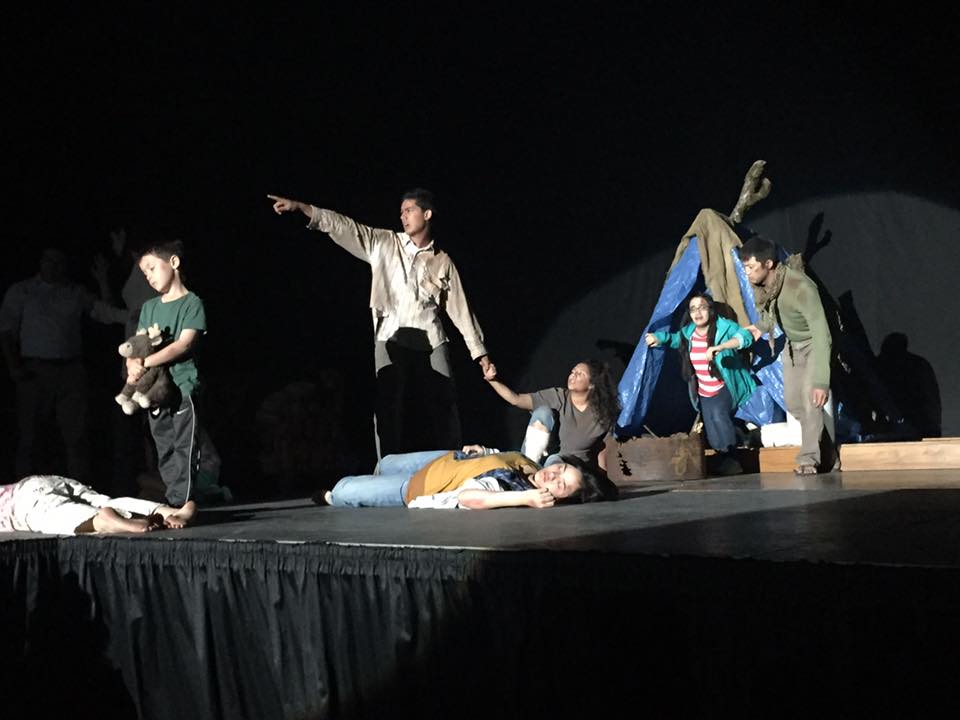

Christ came to save us all: the tattooed and the trucker hatted; the schoolbus driver and the new teen driver; the gun-toting soldier and the refugee. He would not let one fall to the ground without regarding it as precious. Not a sparrow falls without his notice. In the same vein, this flag that we revere, the one we cannot let fall to the ground, is one for which blood was shed so that all could enjoy freedom. What could be freer than love? Freedom and love are regularly compromised and trampled on the battlefield for our hearts, but the war has already been won by the One.

Christ came to save us all: the tattooed and the trucker hatted; the schoolbus driver and the new teen driver; the gun-toting soldier and the refugee. He would not let one fall to the ground without regarding it as precious. Not a sparrow falls without his notice. In the same vein, this flag that we revere, the one we cannot let fall to the ground, is one for which blood was shed so that all could enjoy freedom. What could be freer than love? Freedom and love are regularly compromised and trampled on the battlefield for our hearts, but the war has already been won by the One.